IROS 2022 paper

A Novel Design and Evaluation of a Dactylus-Equipped Quadruped Robot for Mobile Manipulation

Something that’s been bothering me about four-legged robots for a while now is how can we make them useful. Many quadrupeds are marketed for inspection tasks, which a drone could likely do just as well. One thing a legged bot can do better than a drone though is environmental interaction - pushing buttons, pulling levers, carrying objects etc. For this task they are usually given arm payloads with grippers, which take up space and payload capacity, not to mention often costing as much as the robot itself.

The shortcomings of arms and a need for lighter and cheaper manipulation are starting to become apparent in practice. For example, in the AIRA 2022 challenge, which featured navigation and locomotion tasks for legged robots, teams needed to swap between SLAM payloads and arms to complete all required tasks. Although this is fine for an academic environment, in real-world deployment far away from an operator you can’t change payloads. In his ICRA 2022 keynote talk, Marco Hutter (founder of ANYbotics) also brought up manipulation if we want practical quadrupeds.

Another thing of note is the recent interest and progress in the field of two-limbed manipulation. A second arm is very useful when it comes to carrying big objects or providing support, like holding a bottle with one hand while screwing the cap on with the other, and some very smart people have been devising ways to take advantage of 2 arms (that’s also the IROS 2022 Best Paper). It might not be too early to consider having 2 grippers on a quadruped to improve manipulation. Just sticking 2 arms won’t cut it - Spot has a max payload of 14 kg and 2 Spot Arms would weigh 16 kg in total, so a dual-armed Spot could only be useful if your application involves carrying at least 122 helium balloons.

The idea

So, what can we do about it? My thinking went something like this: on a quadruped, we already have 4 legs designed to be both dynamic and precise. Those legs have 3 motors each, capable of carrying a whole body. We are only 4 DoFs away from an arm + gripper, and these DoFs can have smaller and cheaper motors since the leg motors are the ones doing the heavy lifting.

In this case, can we put some grippers on the front legs for one- and two-limbed manipulation?

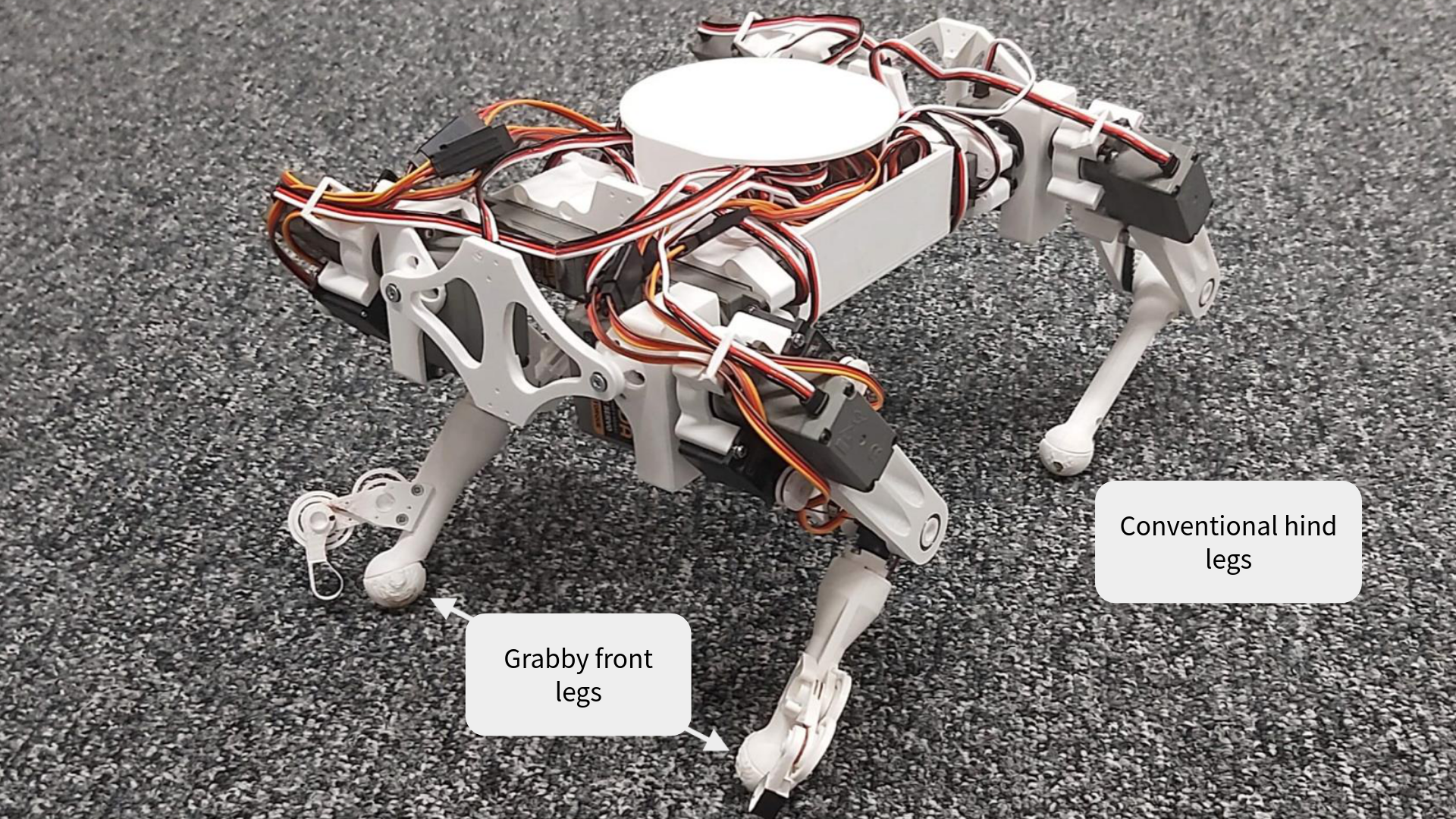

To see how far could this idea go, I made a small-scale quadruped robot with 3-DoF manipulators on its front legs and normal hind legs.

Conventional leg

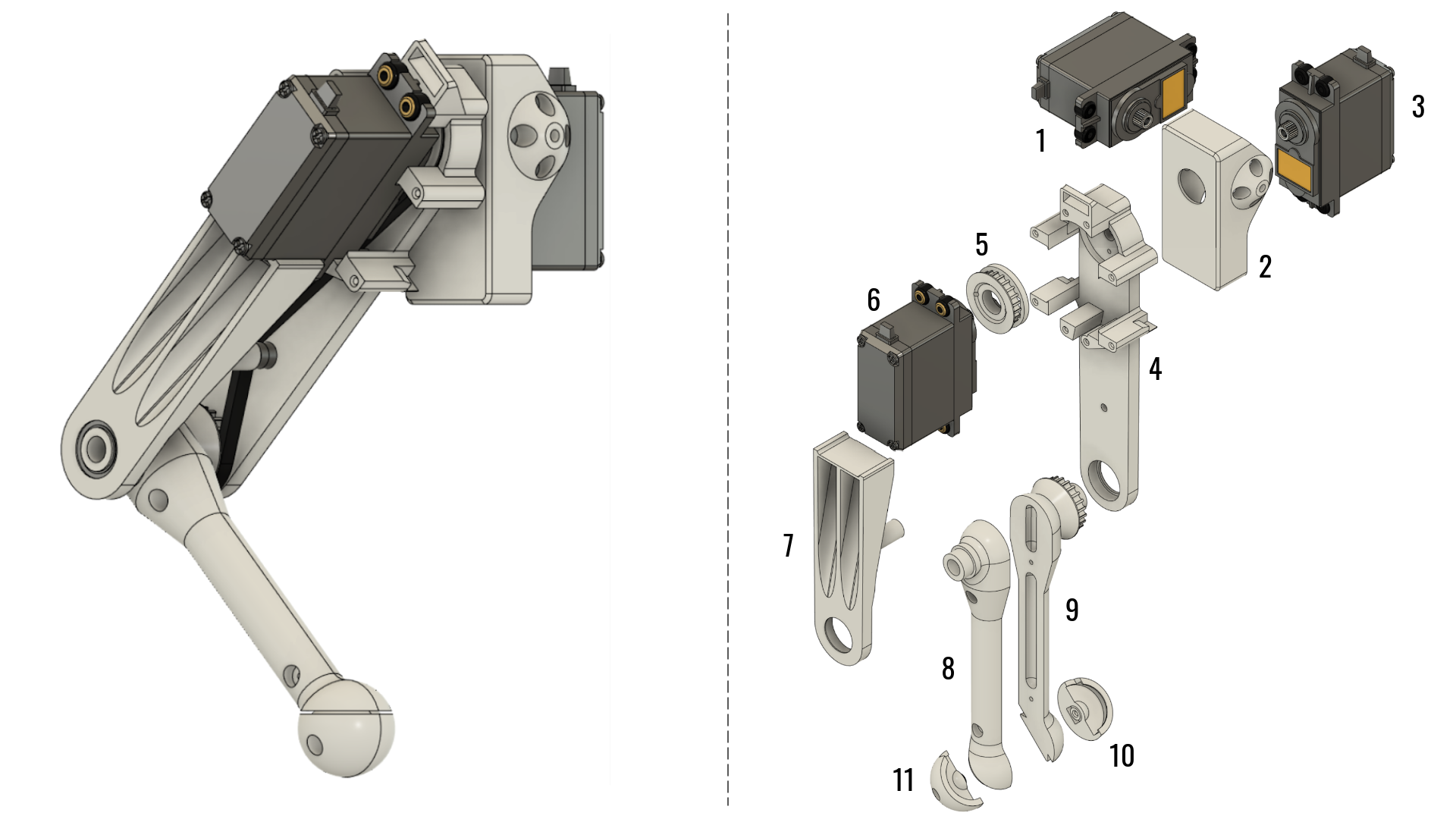

To get to a manipulation-capable leg, we need a normal leg first. Such a leg would need to be light, stiff and the knee should bend both ways to easily grab objects from the ground once it gets a manipulator, therefore I can’t use a four-bar leg design like in Stanford Pupper. For manufacturing, I only had access to a 3D-printer. For actuation, I settled on the Gobilda 2000 Torque since they have sufficient torque and a range of 300°, allowing for the double-bending knee. 2 such motors in the knees should comfortably lift 2 kg from 15 cm away, which was the projected worst case for the mass of a body + 2 legs. Considering the motors, I had the leg sections to be longer than 10 cm, just to not test the motor limits too much.

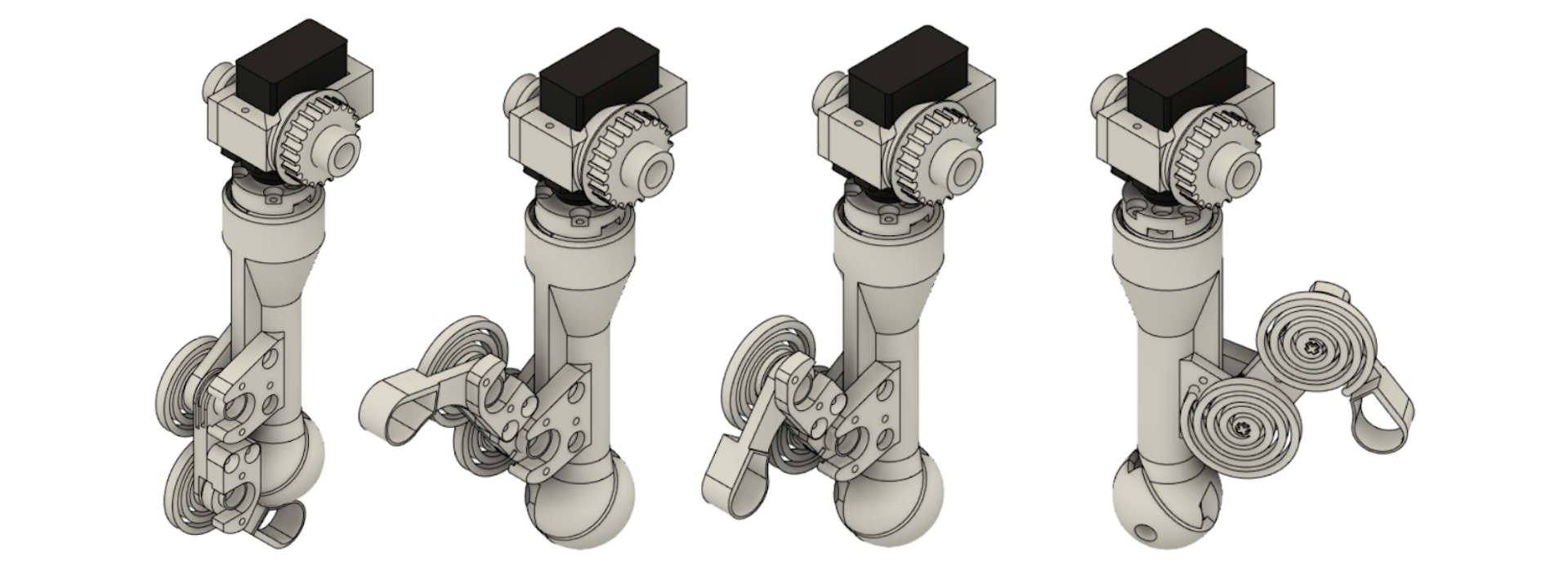

With the design specs out of the way, I ended up with a belt-driven leg:

It’s about 45% or 158 g lighter than OpenQuadruped, the best fully 3D-printed design I found at this scale and it took some heavy falls while testing without breaking, so it did its job. Here are a few interesting design details:

- It prints without slicer supports - there are only 2 tiny ones on the femur (4) that are baked in the model.

- For the knee joint, using 4mm width M3 belts instead of the more common 6mm M2 belts (as with the design I compared against) enables the servo pulley (5) to be mounted under the servo hub instead of over it. This reduces design size and moves the point at which force is applied closer to the base of the shaft, reducing bending stresses.

- The tibia servo motor is integrated as a stress-bearing member, improving leg resistance to side forces.

- The cavities on the inner side of the tibia halves (8-9) add perimeters of material away from the neutral axis, increasing the second moment of area and thus improving stiffness for about the same mass as a part with uniform infill.

- I resorted to directly threading the screws in plastic rather than heat set inserts/captive nuts since they’d add quite a bit of weight while not being that much stronger.

Manipulation-capable leg

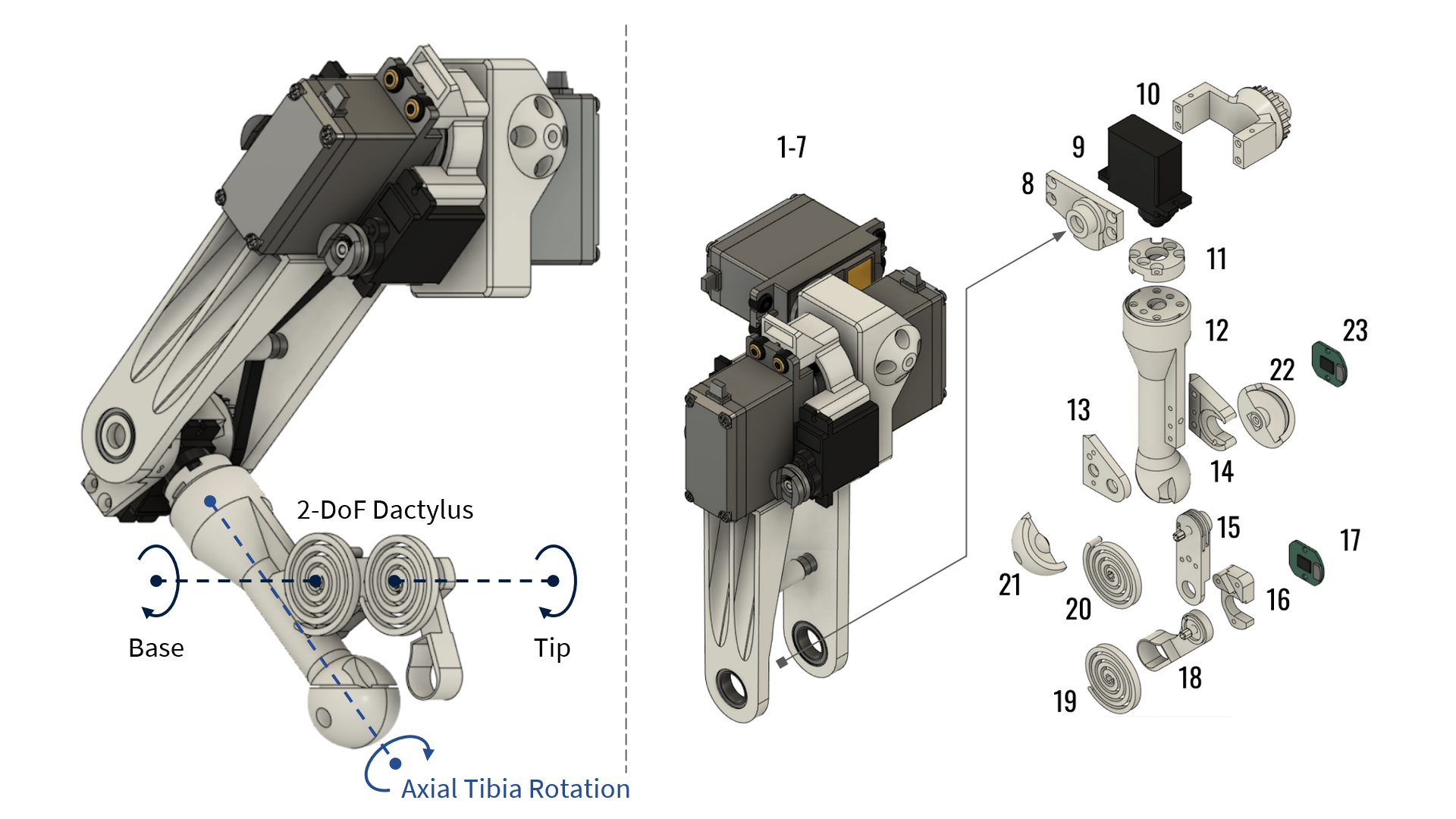

My thinking for how to make the leg grabby was centered on adding a second end effector that can move in 3D relative to the EE of the leg. The idea behind the configuration is probably best demonstrated by this video of a crab eating noodles. You can notice how when it grabs a noodle, only the upper pincer moves, and the lower pincer is just a static extension of the lower limb. If there is a 1-DoF wrist before the claw and we give the moving pincer another DoF, that’s 3 - enough to have the second end effector move in 3D-space, relative to the leg tip.

With this out of the way, here’s the finalised leg:

The motors used for the pincer are these Goteck micro servos. They are really strong and reasonably cheap for their size and their cables come out from the bottom rather than from the back, which allows for a tighter assembly.

The pincer is cable-driven, with 3D-printed spiral torsion springs counteracting the cables. The springs were represented as logarithmic spirals with their parameters generated from the nonlinear constrained optimisation approach detailed in this paper by Scarcia et al.. To do the optimisation, I plugged the equations in MATLAB’s nonlcon. The spring stiffness was chosen to be [max servo torque]/(2*pi) and they were pretensioned to 45 degrees for good holding power while not stressing out the servos too much. I also lowered the max acceptable stress % from 75% to 60 after some spring stress testing, since PLA is more susceptible to creep.

The cables driving the pincer are routed in such a way that they do not experience contraction/extension as the knee joint rotates. They pass through a channel on the knee axis, followed by a conical channel in the tibia and finally reaching the finger. Here’s a GIF that can show it much better than I can put it in words:

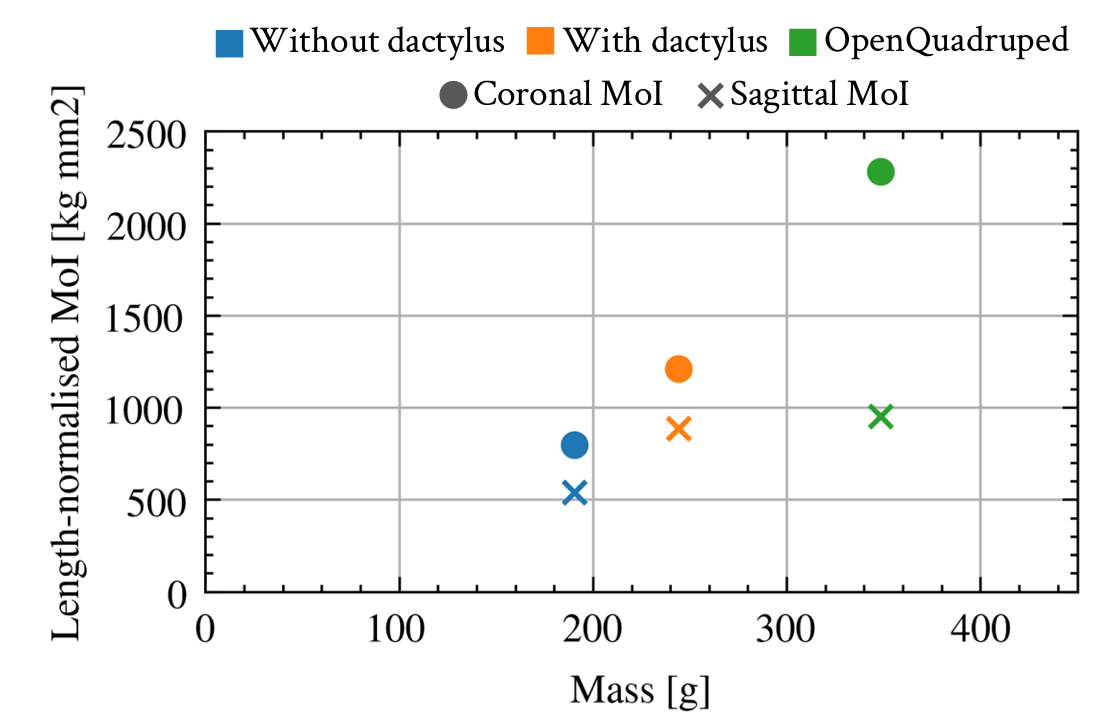

Even with the additional mass, this leg is still 30% or 104 g lighter than OpenQuadruped’s. In terms of moment of inertia (AKA MoI, essentially the rotational equivalent of mass), both grabby and non-grabby legs here are still better, even when accounting for the slightly longer length of OpenQuadruped legs. Here’s a graph to summarise it all:

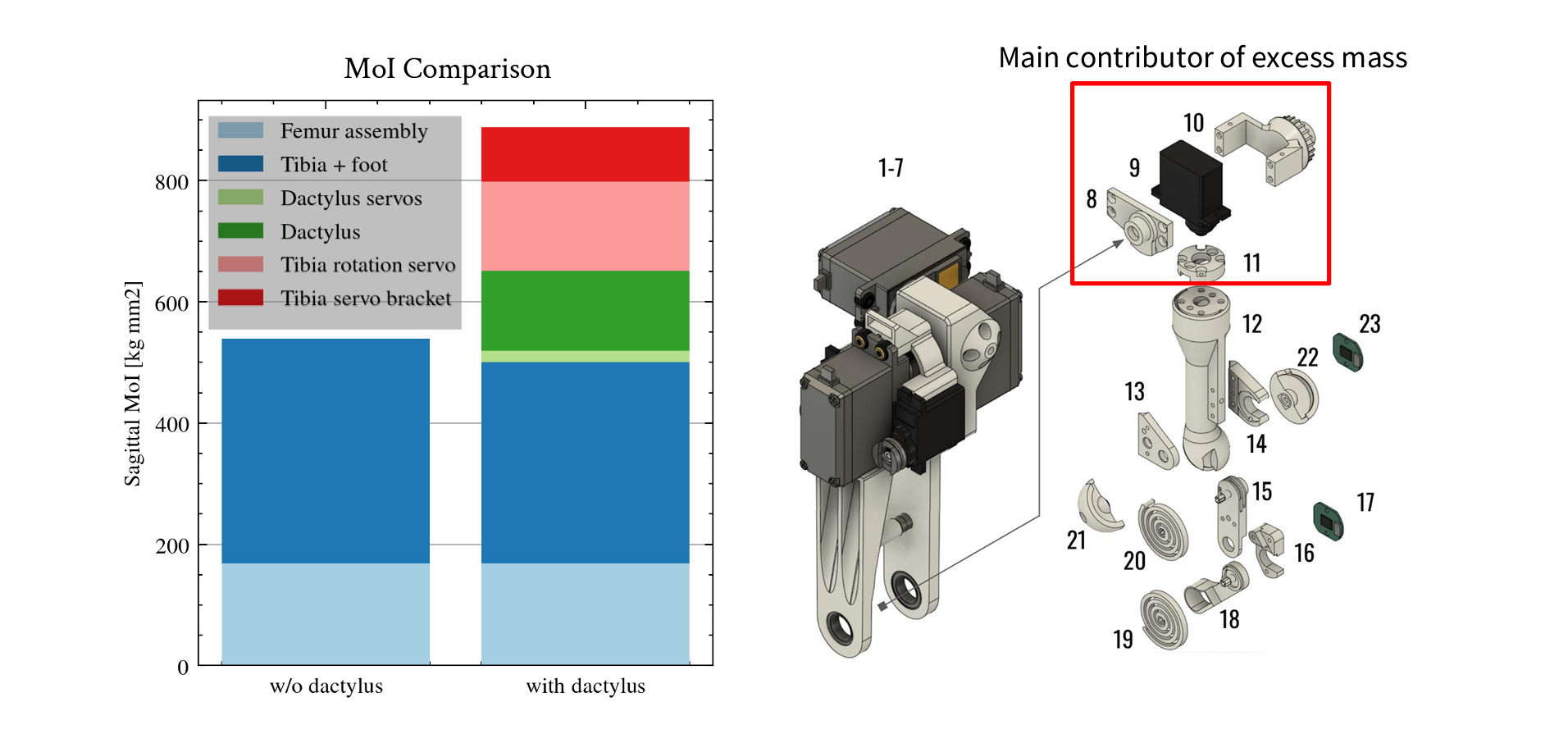

The MoI of the grabby leg is higher than the non-grabby one, which is expected. Looking at the MoIs on a part-by-part basis we can see why:

The majority of the increase comes just from the wrist servo. MoI depends on the square of the distance from the axis around which you measure it, hence why the femur assembly, with its center of mass close to the axis, is not that rotationally heavy. The wrist servo is about 15 g (a fair amount of weight at this scale) and it’s fairly far away, so the increase checks out. Still, wrist servo aside, the pincer and its servos aren’t too bad. I’d wager that at a bigger scale with more space, there is a better solution to this that can make the assembly even lighter.

Another thing to note is the price. At $7.50 per micro servo, the electronics for a single pincer come out at $22.50, while an extra arm and gripper would need 3 Gobildas + 4 micro servos, or $126 at the time of writing. The added masses come out at 54 g and 290 g respectively. Overall, an arm would be about 5x more expensive and 5x heavier than a pincer.

A few words on the assembled robot - it’s powered by a 2-cell Li-Po battery, whose power is distributed by a BEC on a custom power distribution board that plugs onto a Raspberry Pi. The Pi is responsible for the high-level control, while a Teensy 3.5 does the low-level motions. Due to the ongoing chip shortage, I also made it so it can run without a Pi if needed.

Software and testing

I implemented a jerk-continuous motion profile detailed in this paper by Yi Fang et al. for low-level control. It’s just a long, piecewise equation you can integrate 3 times to get a displacement profile. The only cool thing about my implementation is that radially mirroring the profile past the midpoint saves some computational time. As for high-level control, I wanted to implement a Blender-based GUI that allows for more intuitive control, but ran out of time and resorted to manually driving the joints.

Luckily, the manipulators were good enough to compensate for the far-from-perfect control strategy. The robot managed to hold reliably objects of various sizes with a single leg and use wire cutters on some rubber tubing with 2 legs. The footage of the experiments is in the thumbnail GIF and near the end of my IROS 2022 presentation:

What’s next

To my knowledge, this is the first quadruped capable of single-legged manipulation and using tools while using hardware 5x lighter and 5x cheaper than an equivalent conventional arm. The results were promising and now need deployment at a larger scale to explore the possibilities, so I’ll be upscaling it to the ANYmal quadruped in my local robotics lab. I expect the moment of inertia increase to become smaller for an aluminum construction (for a better strength/mass ratio than PLA). Another thing that might help is that motors tend to constitute a smaller % of the total mass as a robot gets bigger (about 52% for this robot, 36% for ANYmal), meaning I might get away with a directly-driven wrist. And that’s not mentioning the much more torque-dense motors one could have access to at a bigger scale. Once the upscaled design is done, it will receive a writeup here, so stay tuned.

There are many small things I’d want to change in the bigger version too. The wrist will need to be redesigned because for a big quadruped, I wouldn’t want to load the ‘wrist’ with the stress caused from carrying the body and the legs impacting the ground. Furthermore, although we can control the grasping point, there is no way to change the orientation of the object on the axis connecting the points of contact since it’s lacking a DoF for this. Maybe whole-body motion can be used to circumvent this lack of a DoF, reducing the cost and complexity, but then this will make the gripper harder to use than an arm payload and thus less desirable… this got complicated quick. Other viewpoints are very welcome here! Feel free to reach out at Y.T.Tsvetkov@sms.ed.ac.uk, I’d love to hear other people’s opinions on this.

Full paper

If you want to read about this work in more detail, you can find a preprint of the paper here. If you have any feedback, don’t hesitate to share it with me at Y.T.Tsvetkov@sms.ed.ac.uk!